Editors’ note: In a world transformed by a pandemic, few of the fundamentals in Americans’ lives – schools, jobs, even how to shop for groceries – have remained the same. The same is true with the election, where the most basic of the institution’s elements – how, where and when to vote, among them – have changed.

When The Conversation US’s politics editors met to figure out how to provide readers with coverage that would be useful and informative, the approach was clear: a civics lesson. Over the course of roughly 100 articles, our scholars have explained how the U.S. election system works, retold the history of how it got that way and examined what effects and significance those mechanisms have for the nation today.

Here, our team has collected all of these articles, divided thematically, from the very beginning of campaigning through what happens after Election Day itself.

Campaigning

Basic elements of political campaigning

- The two-party system is here to stay

- Civility in politics is harder than you think

- George Washington was silent, but Trump tweets regularly – running for president has changed over the years

- The clothes make the candidate: The sartorial politics of this year’s key Senate races

- Why do people believe con artists?

- Angry Americans: How political rage helps campaigns but hurts democracy

Campaigning in a pandemic

- Presidential campaigns take flight in the age of the coronavirus

- Amid pandemic, campaigning turns to the internet

- From recording videos in a closet to Zoom meditating, 2020’s political campaigns adjust to the pandemic

Campaign tactics

- Why you’re getting so many political text messages right now

- What’s the best way to get out the vote in a pandemic?

- Trump’s law-and-order campaign relies on a historic American tradition of racist and anti-immigrant politics

- Trump and Biden ads on Facebook and Instagram focus on rallying the base

Political conventions

- Democratic, Republican parties both play favorites when allotting convention delegates to states

- Political conventions today are for partying and pageantry, not picking nominees

- Pandemic alters political conventions – which have always changed with the times

- What are political parties’ platforms – and do they matter?

Money in politics

- Election 2020 sees record $11 billion in campaign spending, mostly from a handful of super-rich donors

- Money talks: Big business, political strategy and corporate involvement in US state politics

- When presidential campaigns end, what happens to the leftover money?

Candidates’ debates

- Think presidential debates are dull? Thank 1950s TV game shows

- How to make presidential debates serve voters, not candidates

- Lessons on wrangling candidates from the masterful moderator of presidential debates, Jim Lehrer

- Don’t underestimate the power of the putdown in a presidential debate

- Dominance or democracy? Authoritarian white masculinity as Trump and Pence’s political debate strategy

- VP debates are often forgettable – but Dan Quayle never recovered from his 1988 debate mistake

Media and public perception

- Political bias in media doesn’t threaten democracy – other, less visible biases do

- Watch more TV to understand the backlash against the women in the running for vice president

- The candidate you like is the one you think is most electable

- Why is it so hard for atheists to get voted in to Congress?

Polling

- When noted journalists bashed political polls as nothing more than ‘a fragmentary snapshot’ of a moment in time

- Epic miscalls and landslides unforeseen: The exceptional catalog of polling failure

- Political forecast models aren’t necessarily more accurate than polls – or the weather

Vice presidential and Cabinet picks

- For Biden, naming Cabinet before election would be a big risk

- Don’t expect Biden’s pick of Kamala Harris for VP to make or break the 2020 election

- VP pick Kamala Harris stands on many women’s shoulders, especially Bella Abzug’s

- Before Kamala Harris became Biden’s running mate, Shirley Chisholm and other Black women aimed for the White House

International perspectives

- Russian media may be joining China and Iran in turning on Trump

- What could replace the Electoral College?

- What US election officials could learn from Australia about boosting voter turnout

The process of voting

History of voting

- The right to vote is not in the Constitution

- There’s nothing unusual about early voting – it’s been done since the founding of the republic

- 1864 elections went on during the Civil War – even though Lincoln thought it would be a disaster for himself and the Republican Party

- A summer of protest, unemployment and presidential politics – welcome to 1932

Voter suppression

- Closing polling places is the 21st century’s version of a poll tax

- Why the Supreme Court made Wisconsin vote during the coronavirus crisis

- Trump’s encouragement of GOP poll watchers echoes an old tactic of voter intimidation

- Georgia’s election disaster shows how bad voting in 2020 can be

- It takes a long time to vote

- How sexist abuse of women in Congress amounts to political violence – and undermines American democracy

Many voters face obstacles

- Citizenship delays imperil voting for hundreds of thousands of immigrants in the 2020 election

- As few as 1 in 10 homeless people vote in elections – here’s why

Specific voting groups and blocs

- With Kamala Harris, Americans yet again have trouble understanding what multiracial means

- Kamala Harris represents an opportunity for coalition building between Blacks and Asian Americans

- Asian Americans’ political preferences have flipped from red to blue

- Want the youth vote? Some college students are still up for grabs in November

- How to reach young voters when they’re stuck at home

- Will German Americans again put Donald Trump over the top in the presidential election?

- Indian Americans can be an influential voting bloc – despite their small numbers

- With Harris pick, Biden reaches out to young Black Americans

How to vote

- Why there is no ethical reason not to vote (unless you come down with COVID-19 on Election Day)

- Iowa caucuses did one thing right: Require paper ballots

- How to make sure your vote counts in November

Voting in person

- Voting while God is watching – does having churches as polling stations sway the ballot?

- Poll workers on Election Day will be younger – and probably more diverse – due to COVID-19

- 19th-century political parties kidnapped reluctant voters and printed their own ballots – and that’s why we’ve got laws regulating behavior at polling places

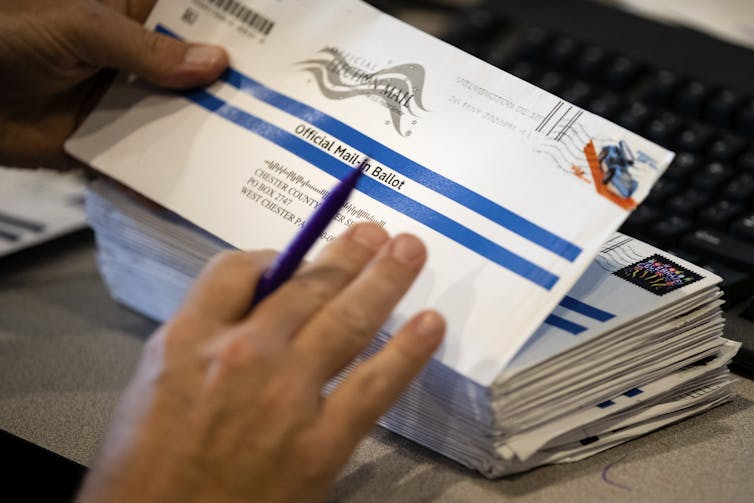

Voting by mail

- Timing, signatures and huge demand make mail-in voting difficult

- Mail-in voting’s potential problems only begin at the post office – an underfunded, underprepared decentralized system could be trouble

- Some states more ready for mail-in voting than others

- 6 ways mail-in ballots are protected from fraud

- Research on voting by mail says it’s safe – from fraud and disease

- Mail-in voting lessons from Oregon, the state with the longest history of voting by mail

- Mail-in voting does not cause fraud, but judges are buying the GOP’s argument that it does

- Voting by mail is convenient, but not always secret

- How to track your mail-in ballot

Aftermath

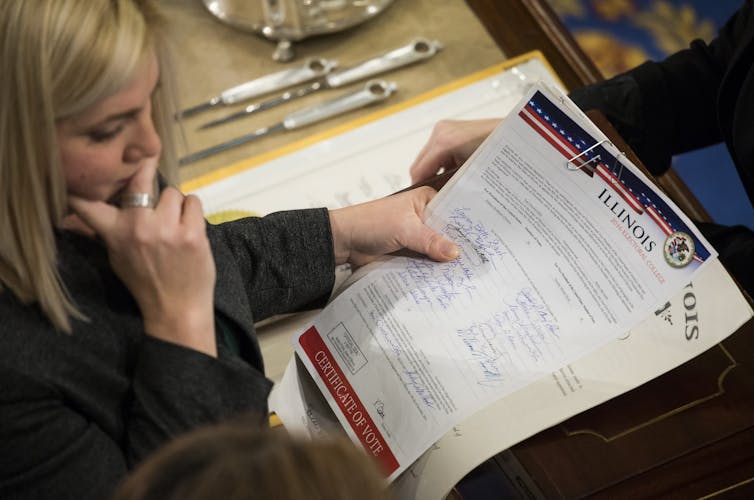

Electoral College

- Electoral College benefits whiter states, study shows

- The Electoral College is surprisingly vulnerable to popular vote changes

- Supreme Court reforms, strengthens Electoral College

Election integrity

- ‘Stolen’ elections open wounds that may never heal

- If Trump refuses to accept defeat in November, the republic will survive intact, as it has 5 out of 6 times in the past

- Judges used to stay out of election disputes, but this year lawsuits could well decide the presidency

Potential for violence

- When politicians use hate speech, political violence increases

- Election violence in November? Here’s what the research says

Who decides the outcome?

- How Congress could decide the 2020 election

- The case of Biden versus Trump – or how a judge could decide the presidential election

- Could a few state legislatures choose the next president?

- Who formally declares the winner of the US presidential election?

How it all ends![]()

Catesby Holmes, International Editor | Politics Editor, The Conversation; Jeff Inglis, Politics + Society Editor, The Conversation, and Naomi Schalit, Senior Editor, Politics + Society, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.