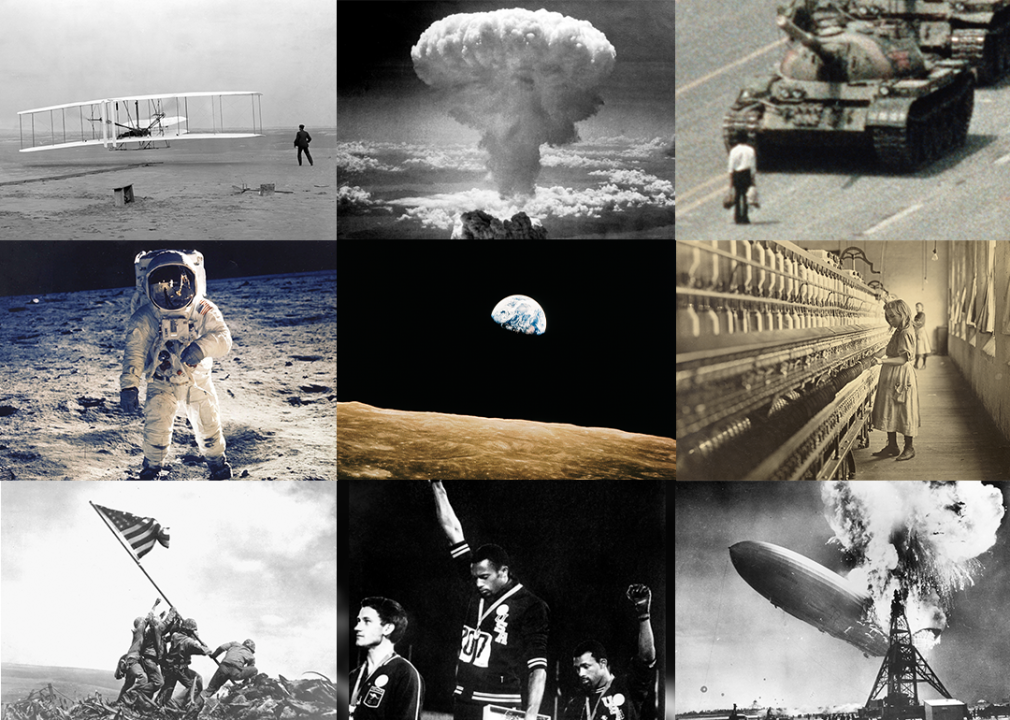

John T. Daniels; Charles Levy Arthur; Tsang Hin Wah; NASA; Lewis Hine; Joe Rosenthal; John Dominis;Sam Shere // Getty Images

Read the original, including images:25 photos that changed the course of history

In an era where any novice with a smartphone can take professional-quality photographs, suffice it to say people are taking a lot of pictures. By one estimate, nearly 2 trillion photographs are captured each year—and more than 55,000 every second around the world. Although photographs have become ubiquitous in an age of selfies and social media, they still possess their timeless power to transport us to faraway places, introduce us to compelling people, and—in many instances—even alter the course of history.

Stacker collected 25 examples of images that changed the course of history, whether by advancing technical abilities of photography that enabled more people to engage in it, or by recording moments, items, people, and events that were made more significant because there were images for people to share.

Prior to its widespread use, photography was a technological puzzle. The effort involved chemistry, physics, metallurgy, and all manner of optical devices. Over the years, the equipment got smaller, lighter, and easier to use. By the late 1970s, tens of millions of cameras were sold around the world every year. Since then, the advent of digital photography and the spread of the aforementioned camera-equipped smartphones have put cameras into the hands of more than two of every three people on the planet, according to an industry analysis by Statista.

Photographs and the people who make them have helped billions of people better understand our world and what lies beyond it. Keep reading to discover 25 images that helped shape human perception and understanding of the last 200 years.

View from the Window at Le Gras - Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (c. 1827)

The oldest surviving photograph ever taken took eight hours to expose and shows a view of buildings and trees from a window on the photographer Joseph Nicéphore Niépce's estate.

It marked the beginning of a technological and chemical revolution that led to several other methods of registering images based on chemical reactions that occurred when light hit a specially prepared surface.

Boulevard Du Temple, Paris - Louis-Jacques-Mande Daguerre (1838)

Made by Louis-Jacques-Mande Daguerre, this daguerreotype—an image printed on a silvered copper plate—is believed to be the first photographic image including a living person. Because of the long exposure time required, what would have been a bustling street appears empty except for a person standing still in the lower left, getting his shoes shined by a crouching figure.

Lower Falls, Yellowstone National Park - William Henry Jackson (1871)

William Henry Jackson captured this striking image of the Lower Falls while on an expedition to explore northwestern Wyoming. Reports of what Jackson's group found—geysers, waterfalls, and other geologic wonders—were so incredible the public didn't believe them until photographic proof was made available.

Jackson's photographs of the Lower Falls and other natural wonders in the region helped persuade Americans and Congress to create Yellowstone National Park, the world's first national park.

The Horse in Motion - Eadweard James Muybridge (1877)

This set of photographic images truly paved the way for the film industry.

Eadweard James Muybridge's photos froze time in increments of 1/500th of a second. The photographer achieved this feat by capturing a series of images triggered on separate cameras by tiny threads broken by a moving animal or clockwork system. In addition to settling a controversy of the time—whether a horse ever lifted all its legs off the ground when galloping—Muybridge's work showed people the value of viewing sequences of images taken at short intervals.

Lodgers in Bayard Street Tenement, Five Cents a Spot - Jacob August Riis (1889)

Jacob Riis was an early investigative photojournalist whose 1890 book "How the Other Half Lives" documented the lives of people who lived in the slums of New York City. The book exposed the squalor of the city's tenement dwellings, including this room less than 13 feet long that was home to 12 men and women. The image sparked an investigation into housing conditions and is widely credited with sparking significant social reforms. Riis' legacy is that of being among the first to energize a social movement using photography.

The Wright Brothers First Flight - John T. Daniels (Dec. 17, 1903)

The Wright Brothers were the first to invent a flying vehicle. But to be believed, they needed proof—and proof, less than a century after the earliest recorded photograph, meant snapshots. The brothers set up cameras for all their tests and experiments, but timing was everything. Sometimes they got just a shot of the sky. This time—their first flight, at 10:35 a.m. on Dec. 17, 1903—the timing was perfect, capturing the first flight that was powered, sustained, and controlled.

Sadie Pfeifer, Cotton Mill Spinner - Lewis Wickes Hine (1908)

Inspired by Jacob Riis, Lewis Hine was another photographer who worked for social justice. Hine visited farms, mills, and factories around the country during his work for the National Child Labor Committee, a group that sought to protect children from dangerous working conditions. He photographed children performing tasks they did every day, including Sadie Pfeifer. Pfeifer was 4 feet tall and likely around 9 years old when she was photographed in front of rows of spools in a cotton mill.

Riis' images helped lead to the passage of the country's first laws protecting child workers.

Migrant Mother - Dorothea Lange (March 9, 1936)

One of many iconic photographs made by Depression-era documentary photographer Dorothea Lange, "Migrant Mother" perfectly captures the impact of economic catastrophe on real people's lives. While working for the Farm Security Administration, Lange employed classical artistic principles to draw people's attention to her subjects and their meaning. Her techniques are on full display in this image of destitute pea-picker Florence Owens Thompson, a 32-year-old mother of seven at the time of the photograph.

The image ran in the San Francisco News within days of Lange creating it and quickly became synonymous with Depression-area destitution. Following the photo's publication, the U.S. government sent 20,000 pounds of food to the pea-pickers camp (where Thompson was living) in Nipomo, California.

The Hindenburg Disaster - Sam Shere (May 6, 1937)

The explosion of the Hindenburg in Lakehurst, New Jersey, on May 6, 1937, spelled the end of passenger travel by Zeppelin-style airships. That might not have been the case but for this image, as well as video taken of the tragedy.

Terrifying in its magnitude, and the presumed deaths of many aboard, the image was among the first to show a real failure of advanced technology, highlighting the dangers of the future's promise.

Raising The Flag On Iwo Jima - Joe Rosenthal (Feb. 25, 1945)

Millions saw this famous photograph in newspapers and magazines around the world at the time but also memorialized in bronze at the Marine Corps War Memorial in Washington D.C. It symbolized American fighting strength during the grueling Pacific campaign of World War II and a premature declaration of U.S. triumph over Japanese forces.

Among all the Pacific islands where the U.S. fought Japan, Iwo Jima was the first ruled directly by the Japanese government. Initially, this was seen as a harbinger of victories to come, but the war dragged on for bloody, deadly month after bloody, deadly month.

Historians reflected that the photo made the American public impatient for victory, and therefore more likely to support the terrible destruction of the nuclear attacks on Japan.

Liberation of concentration camps (1945)

As American troops rolled west across Germany in 1945, they encountered prison camps. The camps held horrors so shocking that Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, then the supreme commander of all Allied forces in Europe, insisted on bringing top military brass, journalists, photographers, American political figures, and others—including local residents—to see for themselves what had happened.

The goal for such documentation was to bear public witness, at the time and for all of history, to the horrors of the Nazi regime and the Holocaust.

Mushroom Cloud over Nagasaki - Lieutenant Charles Levy (Aug. 6, 1945)

Only a few people prior to Aug. 6, 1945, had ever seen a nuclear explosion. On that day, when the U.S. dropped the first-ever nuclear attack on Hiroshima, Japan, vast numbers of those who witnessed it died. Three days later, when the U.S. dropped its second bomb on Nagasaki, a member of the flight crew of a plane accompanying the one that dropped the bomb used his personal camera to reveal the massive power of the new weapons. His photograph recorded the 45,000-foot-high mushroom cloud rising over a city where as many as 80,000 people had just died—and many more would die in the coming years from the aftereffects of radiation exposure.

Many other photos of the attacks were censored, but Lt. Charles Levy's image spread worldwide and introduced the mushroom cloud concept.

Emmett Till Funeral - David Jackson (Sept. 15, 1955)

This photo shows Emmett Till just months before white supremacists brutally murdered him in August 1955; at age 14, Till was killed by people who claimed he may have whistled at a white woman in a Mississippi town while on vacation from his home in Chicago.

His lynching and funeral became a key moment in the Civil Rights Movement, in part because his mother insisted on having an open-casket funeral so everyone could see what had been done to the teenager. David Jackson's horrific image of Till's body, first published in Jet magazine and subsequently more widely distributed, shocked the nation into a deeper awareness of the brutality of racism. An all-white, all-male jury acquitted two white men of his murder in September 1955, but calls for justice continued for decades. The FBI closed the case in 2021—66 years after Till's death—upon concluding it could not prove the woman who had reported Till's alleged whistling had lied.

Guerrillero Heroico - Korda (March 5, 1960)

Cuban photographer Alberto Diaz Gutierrez, better known as Alberto Korda or simply Korda, is pictured here with a print of his iconic portrait of Ernesto "Che" Guevara, an Argentinian Marxist who fought alongside Fidel Casto in the Cuban Revolution. The image did not become famous until Guevara died in 1967, at which point it spread around the world on banners, T-shirts, college dorm posters, stickers, and many other printed materials. In many ways, the portrait is one of the earliest viral images, appearing in all manner of places and uses, peering ferociously into an uncertain future.

Burning Monk - Malcome Browne (June 11, 1963)

The Vietnam War gave rise to many protests, including this act of self-immolation by Buddhist monk Thich Quang Duc in Saigon in June 1963 in protest against the division of Vietnam into north and south. The image—and the act it depicted—shocked the world and reportedly prompted President John F. Kennedy to re-examine the U.S. role in Vietnam, which had until that point been relatively small and advisory. Within a few months, the U.S. backed a coup to overthrow the South Vietnamese government; by the end of 1964, Congress authorized President Lyndon B. Johnson to expand the U.S. military's role in the fighting.

Vietnam Execution - Eddie Adams (Feb. 1, 1968)

Eddie Adams won the 1969 Pulitzer Prize for Spot News Photography for his image of South Vietnamese Gen. Nguyen Ngoc Loan summarily executing Viet Cong fighter Nguyen Van Lem in Saigon on Feb. 1, 1968. Military analysts later determined that Adams had pressed the shutter on his camera when Loan pulled the trigger. The image, which Adams was conflicted about for the rest of his life, became a symbol of the war's brutality and was used by antiwar protesters in the U.S. to garner more support for ending the war.

Olympics Black Power Salute - John Dominis (October 16, 1968)

Athletes have long used their platforms to make social-issue stances. When U.S. sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos won gold and bronze, respectively, for the 200-meter race in the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, they raised their black-gloved fists on the medal stand during the playing of the "Star-Spangled Banner" to show solidarity with the plight of Black people in the United States.

The silver medal winner, Peter Norman of Australia, did not raise his fist but supported their gesture. For the medal ceremony, he not only recommended they each wear just one glove—they only had one pair with them—but also a button saying "Olympic Project for Civil Rights" given to him by Smith and Carlos. All three found themselves banned from their nations' Olympic teams, just one consequence of their stands for equality.

Earth Rise - Bill Anders (Dec. 24, 1968)

When the astronauts aboard Apollo 8 orbited the Moon on Christmas Eve 1968, they were surprised and moved by a view of the partially illuminated Earth emerging above the lunar landscape. They scrambled to grab a camera containing color film before the angle changed too much.

Bill Anders got the shot of a fragile world in a sea of space, which sparked a massive environmental movement and is credited with inspiring the first Earth Day in 1970. It has been followed by other views from space to give perspective to those on Earth, including the "Pale Blue Dot" image taken from Voyager 1 in 1990, which was one part of the "family portrait" of six of the solar system's planets.

Man on the Moon - Neil Armstrong (July 20, 1969)

Neil Armstrong, the first person to walk on the Moon, took this picture and also appears in it, reflected in the visor of Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin during the first lunar landing. Also reflected in Aldrin's visor are the "Eagle" landing module, where astronaut Michael Collins remained while the other two men walked on the Moon's surface, the U.S. flag they planted there, and even Earth itself as a little blue dot in the lunar sky.

Kent State Shooting - Howard Ruffner (May 4, 1970)

John Filo's iconic image of 14-year-old Mary Ann Vecchio screaming over the body of Jeffrey Miller, one of four people shot dead by the Ohio National Guard during protests against the Vietnam War at Kent State University, gave Americans a sense of the horror and tragedy clearly felt by witnesses, photographed here by Howard Ruffner.

Filo and Ruffner, like Miller, were students at Kent State. Vecchio was visiting the campus.

Napalm Girl - Nick Ut (June 7, 1972)

Known formally as "The Terror of War," a Huynh Cong "Nick" Ut photo of Phan Thi Kim Phuc and other children fleeing from a U.S. attack on their village in Vietnam drove home—again—the human cost of the Vietnam War.

Phan Thi, then 9 years old, was badly burned by napalm. Ut won the 1973 Pulitzer Prize for Spot News Photography for the image, which he credits with drawing enough publicity to save Pan Thi's life. The little girl spent 14 months in hospitals and was used by Vietnam's communist leaders as an antiwar propaganda figure. In 1992, she was granted asylum by Canada and began a foundation to aid children who are victims of war. This image is of her speaking to an audience in Japan, with the famous image of her projected behind.

Princess Diana with AIDS patient - Anwar Hussein (April 9, 1987)

Among her many humanitarian efforts during her tragically short life, Princess Diana advocated for people with HIV and AIDS. In the 1980s, the virus and the disease were frightening, leading to ostracism of patients, in part because many people did not understand how the disease was transmitted. Health care workers were advised to take so-called "universal precautions" including gloves, masks, and even goggles while working with HIV/AIDS patients.

Diana's simple act of shaking hands with a patient with HIV/AIDS—sitting near him and personally touching him, without gloves—made a clear statement that despite their illness, people with these conditions were safe to be around and interact with. Her striking act of deep humanity helped shift public sentiment away from fear and toward compassion for people with HIV/AIDS.

Tank Man - Multiple photographers (June 5, 1989)

Student protests in the spring of 1989 grew across China, demanding the country's communist government provide greater political freedoms and higher standards of living to its people. Protestors' presence in Tiananmen Square, in the heart of Beijing—along with their pro-democratic activities and the sheer length of time they occupied a key civic and cultural landmark—sparked a military response in early June. As tanks rolled in—ultimately killing hundreds, at least—a lone figure carrying a couple of shopping bags, stepped in front of a line of tanks and just stood there. The tank tried to move around him, with the person moving to remain in front of it until two people, presumably police officers, took him away.

Four photographers captured similar versions of the scene: Eddie Cole, Stuart Franklin, Jeff Widener, and Arthur Tsang Hin Wah. No one has ever definitively identified the man who defied an armored column of troops, nor his fate.

Alan Kurdi - Nilüfer Demir (Sept. 2, 2015)

As the multi-year Syrian civil war dragged on into 2015, millions of people were driven from their homes by fighting.

Many escaped to Turkey, ultimately hoping to make it to Europe or North America. In overcrowded boats, the desperate refugees tried to cross the Mediterranean Sea to Greece. Many did not make it.

The body of 3-year-old Alan Kurdi, a Syrian Kurd, washed up on a Turkish beach after the small boat he and his family were in capsized. The photograph put a name and a child's face on what had been a faceless crisis far away from the U.S. and even many Europeans. It galvanized public attention on the Syrian refugee crisis and sparked donations and international political engagement in helping the refugees.

Black Hole - Event Horizon Telescope Project (2019)

Until 2017, nobody had ever seen a black hole. Albert Einstein predicted a black hole to be a collapsed star so extremely dense and with a gravitational field so strong that even light could not escape.

In 2017, an international collaboration of Earth-based telescopes focused its collective attention on the center of M87, a galaxy about 54 million light-years from Earth but large and bright enough that it can be seen through a small telescope on the ground. Putting all their data together formed an image released to the public in 2019 showing a ring of light emitted by matter moving around in an intense gravitational field, with a dark central area.

The perimeter of the black hole can be seen where the light stops and the darkness begins. It is confirmation of more of Einstein's work, a massive breakthrough in humanity's technical and conceptual abilities to explore the universe, and a reminder of how much more there is for people to explore and understand.