In the 2024 election, the two major-party campaigns and many news reporters are spending a lot of time talking about independent voters – those who are neither aligned with the Republican Party nor the Democratic Party. Despite the power that political independents are anticipated to have over the election results, there’s a lot that remains unknown about this group.

The Conversation U.S. has published several articles about what is known, and why it’s hard to know much more. Here are selections from some of those articles:

1. How many independent voters are there?

It’s very hard to answer that question, wrote Thom Reilly, a professor of public affairs at Arizona State University. Part of the problem is figuring out how to define who independent voters are. Surveys often ask people if they are Republicans, Democrats or independents, and if they answer that they are independents, the surveys ask how strongly they might lean toward one party or the other. But this muddies the waters of political identity, Reilly wrote:

“It’s possible that some voters identify as independent but really just have weaker political preferences than party die-hards, while still maintaining some loyalty to one party or the other. And some independent voters change their political identification from one cycle to another. That makes it hard to tell who an independent voter is and how many of them exist.”

Those changing alignments, Reilly wrote, “may require scholars, media outlets and the public to shift their traditional two-party view of American politics.”

2. Independent voters think for themselves

Independent voters exhibit a key quality that most Americans expect of their fellow citizens: They base their views on their life experiences.

Unfortunately, as politics scholars Shanna Pearson-Merkowitz at the University of Maryland and Joshua J. Dyck at UMass Lowell explained, this is an attribute almost unique to political independents:

“In contrast, Democrats’ and Republicans’ ideas of what problems deserve government attention and how to solve them are much less likely to be based on their own life experiences, and instead simply mirror the information they have gained from leading political figures on social media, on cable news networks or through other partisan information outlets.”

For instance, independents living in neighborhoods with high levels of gun violence are far more likely to report being concerned about gun violence than independents who live in safer areas. But, Pearson-Merkowitz and Dyck wrote,

“for Democrats and Republicans, there is no relationship between where they live and their level of concern about gun violence: Whether they live in a relatively dangerous community or a relatively safe one, their views on gun violence reflect their party’s messages on the issue.”

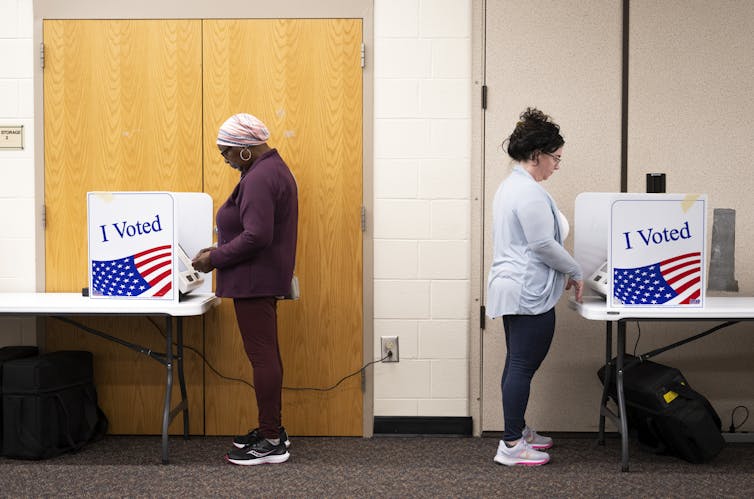

3. Independents less likely to engage in any politics

Research into independents’ political activity finds them tending to stay away from politics, wrote Julio Borquez, a political science scholar at the University of Michigan-Dearborn:

“Perhaps most importantly, pure independent voters are simply less likely to vote than those who express any degree of partisan attachment. In the 2020 presidential election, reported turnout among pure independents was about 20 percentage points lower than turnout among other voters, including independents who lean toward a party.”

Research has found members of this group “tend to be genuinely put off by partisan conflict and party labels,” Borquez wrote. Different studies have found, for instance, that they prefer photos of neighborhoods that did not show political yard signs over the same photos of the same neighborhoods with homes displaying political yard signs. And they pay less attention to campaigns and partisan social media than people with partisan affiliations.

So they are indeed independent – but the question remains whether they will be uninvolved in 2024 or motivated to cast their ballots and make their views known.![]()

Jeff Inglis, Politics + Society Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.