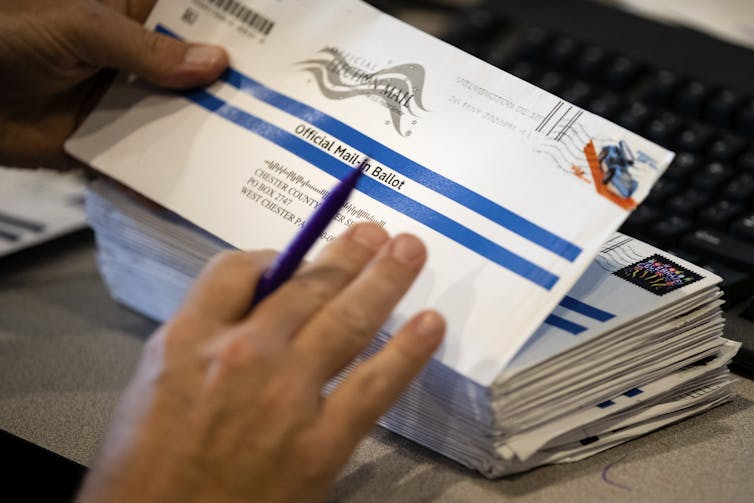

Time is running out for Americans who want to cast their ballots by mail.

If you want to vote this way but haven’t yet requested a ballot, you should know that it takes time for ballot requests to get from voters to their local election officials, for ballots to get mailed to the voters, and for the completed ballots to make it back to election offices.

The U.S. Postal Service recommends that, this close to the election, people who want to vote by mail request their mail-in ballots as soon as they can, and fill them out and send them back in the mail as soon as possible, as well – before Election Day for sure, but perhaps even earlier, depending on state deadlines.

Many scholars have studied various aspects of mail-in voting, looking at how secure it is, how susceptible to fraud it might be, and what voting officials need to do to handle an influx of ballots arriving by mail. Here we spotlight five recent examples from our archives.

1. Mail-in voting is safe and reliable

In 43 states and the District of Columbia, any citizen can vote by mail.

Edie Goldenberg, a University of Michigan political scientist and public policy scholar, studied mail-in balloting as part of a National Academy of Public Administration working group. Her group found that “voting by mail is rarely subject to fraud, does not give an advantage to one political party over another and can in fact inspire public confidence in the voting process.”

2. Election officials and postal workers are key

Many of the protections that keep mail-in voting safe are “built-in safeguards,” according to Charlotte Hill, who is a former elections commissioner now studying voting laws at the University of California, Berkeley, and Jake Grumbach, a political science professor at the University of Washington.

They explain that special paper, printing details, unique bar codes and other anti-counterfeiting methods in election and postal offices combine to “make it hard for one person to vote fraudulently, and even more difficult to commit voter fraud on a scale capable of swinging election outcomes.”

3. It has bipartisan support

Public confidence in voting by mail is extremely high in Oregon, which has been conducting all elections that way since 1998, writes Priscilla Southwell, a professor emerita of political science at the University of Oregon.

She has been studying mail-in voting for almost that entire time, and has been struck by the degree of public support for continuing to conduct elections that way, writing:

“Perhaps the strongest evidence that the system is equitable, fair, reliable and safe is that in two statewide surveys I have conducted over the years, a nearly identical percentage of Oregon Republicans and Democrats strongly support voting by mail, and the same is true of elected officials in the state.”

4. You can keep an eye on things

If you are voting from home, you can make things easier for the people who will be processing and tallying your vote – and those of countless neighbors. Luke Perry, a government professor at Utica College, explains that sending in your ballot early, with a signature that matches the one on your voter-registration card, can ensure your ballot is counted efficiently.

Perry points to an important step voters themselves can take: tracking their ballots. In 44 states and the District of Columbia, people who vote by mail can go online to a statewide site that will display when a ballot has been requested, when it has been mailed to the voter, when it was returned to the election office, and whether it was accepted or rejected. In the remaining six states, some municipalities or counties may provide this option as well – which might allow people whose mail-in ballot was rejected to cast a ballot another way instead.

“This helps people feel confident their vote has been counted and may give them enough notice to vote in person if their mail-in ballot encounters delays or other problems,” Perry writes.

5. Be sure to vote alone

One thing to be aware of, write Susan Orr and James Johnson, is that voting is still supposed to involve a secret ballot.

Orr, who teaches political science at The College at Brockport, a part of the State University of New York system, and Johnson, who teaches political science at the University of Rochester, warn that there are powerful interests seeking to coerce people into voting particular ways.

“In 2018, Los Angeles landlords threatened tenants with rent increases if a particular ballot initiative passed,” they write. “And in the last two presidential elections, as many as 1 in 4 workers were approached with political information by their employer. … [That] included employer endorsements of referenda or candidates – and even notes in employees’ paychecks threatening layoffs or plant closures if one particular candidate were to win.”

They explain that the key element of democracy that prevents these efforts from controlling the results of an election is the principle of a secret ballot. So if you choose to vote by mail at home, make sure you mark and seal your ballot in private.

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives.![]()

Jeff Inglis, Politics + Society Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.