Published in The Emancipator (a joint venture between the Boston Globe and the Boston University Center for Antiracist Research)

The Confederate States of America, the short-lived rogue collection of states addicted to slavery and its profits, will finally be put in its place, if the U.S. Department of Defense has anything to say about it. And a commission that has identified 1,111 items under military control — bases, buildings, streets, signs, and even a floor mat — most certainly does.

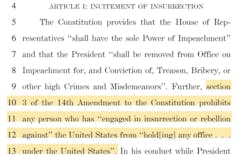

Findings from the Naming Commission that first met in March 2021 revealed a wide-ranging inventory of locations, items, and even software in military use around the globe. The goal is to remove all official commemorations of the Confederacy, “an act of rebellion. It was an act of treason,” according to Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Gen. Mark Milley.

The commission is chaired by retired Adm. Michelle Howard, the first Black woman to command a U.S. combat ship, the first Black woman to hold two-star and three-star admiral ranks, and the first Black person and the first woman to serve as vice chief of naval operations, the second-highest-ranking officer in the Navy. Most of the items are spread across 26 states. This includes seven states on the Union side and three that were not yet states at the time of the Civil War.

There are also items in Washington, D.C. — the Union’s capital city then and our country’s capital now. Still others are at U.S. military installations in Germany and Japan, which were not established until after World War II. These, of course, are not all of the monuments and memorials around the United States that commemorate the Confederate cause.

These symbols don’t exist as a result of accidents or coincidences. Nor were they part of efforts in the immediate wake of the war to “bind up the nation’s wounds,” as President Abraham Lincoln described it. They were created in the early years of the 20th century and remain echoes of a decades-long campaign to recast Confederate history. The real Big Lie, these efforts taught that the Confederacy was a noble “lost cause” attempt to maintain traditional American values, rather than a treasonous insurrection seeking to preserve slavery and the economic engine powered by the forced labor. The commission itself declared, “these names speak far more to the times, places and processes that created them than they do to any actual history of the Civil War, the Confederate insurrection, or our nation’s struggle over slavery and freedom.”

The military base names were among many — honoring both Union and Confederate figures — given to training camps assembled hastily in the run-up to both world wars. Spread around the nation for convenience and political reasons, their names were often picked by local officials who sought to honor their community’s history. Most of the camps, regardless of their namesakes, closed after the wars. But some remained and grew in size and importance over time.

Confederate symbols lurk in many corners

On the commission’s list are nine military bases named for Confederate generals. New names have already been proposed for these locations, subject to approval by Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin III. The recommendations include changing the name of Fort Bragg in North Carolina to Fort Liberty, to capture the American ideal.

The other proposed names honor figures in U.S. military history. Dr. Mary Edwards Walker, for example, is the only woman to receive the Medal of Honor for her efforts to save wounded soldiers during the Civil War. Sgt. William Henry Johnson, a member of the first all-Black U.S. Army unit to fight in World War I, was belatedly awarded the Medal of Honor for single-handedly resisting a German attack. Gen. Richard Cavazos was the first Hispanic American to become a four-star general in the Army.

One other military base, Fort Belvoir in Virginia, is named for a plantation where enslaved people were imprisoned and worked. But because it is not named for a specific Confederate figure or event, the commission has determined the fort is outside its purview. The commission has recommended Pentagon officials rename it under the standard process for renaming of military installations.

Seven vessels are listed. One is a Navy warship named for a Civil War battle won by the Confederate army. Five others are landing craft operated by the U.S. Army and named for Confederate military victories.

The remaining one is an oceanographic survey ship, USNS Maury, named for Matthew Maury, who served in the U.S. Navy starting in 1825. He mapped currents and prevailing winds in ways that dramatically increased the speed of sailing. For that work, he is known as the father of modern oceanography and naval meteorology. However, in 1861, he resigned his commission in the U.S. Navy and joined the Confederate navy.

The inventory also details 14 markers, monuments or statues; 53 paintings, plaques, or portraits; 742 signs, maps, marquees, or displays; and a single floor mat at the Fort Lee commissary. It also includes specific screens in military computer systems, logos on vehicles, and other administrative changes.

The commission recently added references to military units’ battle flags, used at formal events and special occasions to signify the units and their heritage. The flags are often decorated with ribbons for particular awards the unit has earned or identify battles the unit has fought. An August 2022 inventory update added the battle flags of 48 units, which bear a total of 491 streamers commemorating the participation of those units, or their historical predecessors, in battles as part of the Confederate army, though now they are part of the U.S. military.

A September 2022 update recognized that symbols within the insignia for several units, such as a saltire — the X-shaped cross that forms part of the Confederate battle flag — and even the color gray were in some cases meant to honor the Confederacy.

Academy buildings honor traitors

Several of the items on the list are at places where the nation’s top military leaders are trained. They raise questions about how to honor U.S. history without glorifying the treason and rebellion of the Confederacy because the locations and items are named for people who distinguished themselves during loyal service to the U.S. military. They are also the same people who resigned their U.S. commissions to serve in the Confederate military, complicating any formal recognition of their roles in American history.

Consider Maury Hall at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, which is named for the naval oceanographer.

Take the official residence of the Naval Academy’s superintendent, and the street it is on, both named for Franklin Buchanan. He served as a U.S. Navy officer for 45 years, proposed the creation of the Naval Academy, and served as its first superintendent from 1845 to 1847. Like Maury, Buchanan resigned his U.S. commission in 1861 to join the Confederate navy.

The commission has recommended the Naval Academy rename both buildings and the street.

The commission’s inventory lists 10 items at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York. Two are roads named for Pierre Beauregard and William Hardee, academy graduates and longtime U.S. Army officers who both resigned to serve in the Confederate army. The commission has recommended that the roads be renamed.

Seven other items specifically honor 1829 academy graduate Robert E. Lee. They include a barracks, a child-care center, a group of homes, a mathematics award, and images and quotations by him. From 1852 to 1855, he was West Point’s superintendent. In 1861, he resigned from the U.S. Army, joined the Confederate army, and ultimately became the top general.

The commission has recommended that five items be renamed and that one portrait of Lee in his Confederate uniform be removed.

The 10th item on the commission’s West Point list is a public space on campus called Reconciliation Plaza, dedicated in 1961 to “commemorate the reconciliation between North and South.” The plaza includes several markers with engraved images of several Confederate figures, including Lee. Monuments there commemorate the Confederacy, including a depiction of “Confederate forces in insurrection against Fort Sumter, South Carolina,” the event that opened hostilities in the Civil War.

The commission recommended several changes to the plaza, including the removal of the images that depict Confederate figures, and removal or modification of those that commemorate the Confederacy.

The commission’s report also identifies other items at West Point that are not on its inventory list. One is a set of three plaques at the entrance to Bartlett Hall, the academy’s science center, which portrays several Confederate figures, including Lee. The commission has recommended the plaques be changed to remove their names and images.

Additionally, one of the three plaques shows a hooded figure labeled with the words “Ku Klux Klan.” The commission has determined that this monument, like Fort Belvoir’s name, is not connected directly enough to the Confederacy to be under the commission’s authority. But members have nevertheless recommended that the Department of Defense develop policies to handle this and any other such markers or commemorations that may be discovered.

Another item not on the commission’s inventory list is a monument called the Honor Plaza, which includes a quotation from Lee identifying him as Maj. Robert E. Lee, his rank when he served as West Point superintendent. But the quote is from a time when he was serving in the Confederate army. The commission has recommended it and its reference to Lee be removed.

However, the commission has determined that any images or references to Lee during his time as superintendent at West Point and that “do not conflate his Confederate service are historical artifacts and may remain in place.”

There are also plaques inside buildings that depict the names of Fitzhugh Lee and Joseph Wheeler, West Point graduates who served in the Confederacy. The commission has determined those markers commemorate their Confederate service but has left their disposition up to West Point officials.

The commission has not identified any items that honor the Confederacy or Confederate personnel at the other Defense Department academy, the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Its review did not include the U.S. Coast Guard Academy, which is operated by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, nor the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy, which falls under the U.S. Department of Transportation.

What’s next?

The final section of the report recommended all other U.S. Defense Department assets and items — the ones that are not entire bases or housed at military academies — be renamed or have their Confederate-related insignia, markings, or references removed. There is an exception for items not in use, though the commission warned that if those items or insignia return to active use, they should first be altered to remove Confederate references.

The commission also noted that more items, locations, or other military property that honor the Confederacy are likely to come to light in the future. It recommended that those items also be renamed, removed, or modified.

In addition to Admiral Howard, other commission members include Brigadier Gen. Ty Seidule, a professor emeritus of history at West Point; Gen. Robert Neller, a former commandant of the Marine Corps; and Lt. Gen. Thomas Bostick, the first Black West Point graduate to command the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The commission also includes U.S. Rep. Austin Scott, whose district in Georgia contains Fort Gordon and Fort Benning, both named for Confederate generals. Scott notably voted in 2001 to remove the Confederate battle flag from Georgia’s state flag.

Jeff Inglis is a Boston-based editor, writer and data journalist who has covered politics, technology, science and culture in various parts of the U.S., as well as New Zealand and Antarctica.