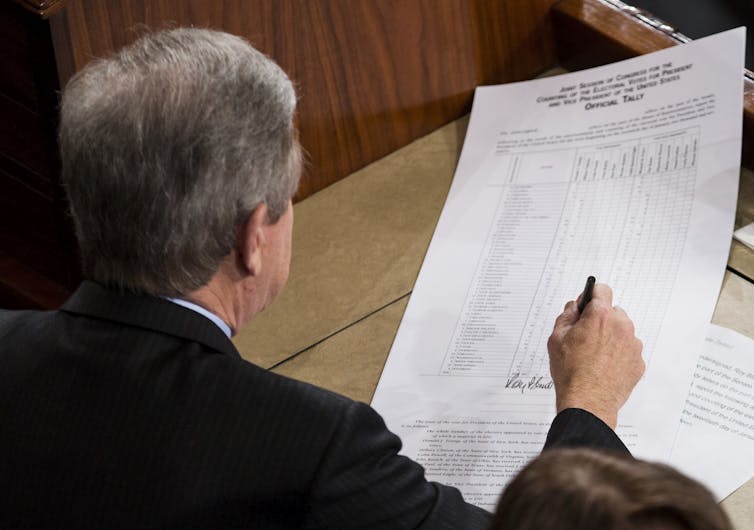

As the U.S. Senate takes up the second impeachment trial of former President Donald Trump, there are a lot of questions about the process and legitimacy of trying someone who is no longer in office, including what the point is and how impeachment works. The House has passed an article of impeachment, charging him with “incitement of insurrection” in connection with the Jan. 6 Capitol riot, and now the process turns to the Senate.

The Conversation has published several articles from scholars explaining aspects of the situation, as well as describing more generally what the purpose of impeachment was for the founders when they wrote the Constitution. This is a selection of excerpts from those articles.

1. Does it matter that Trump is out of office?

The previous three impeachment trials of presidents – of Andrew Johnson in 1868, Bill Clinton in 1998 and Trump himself, the first time, in early 2020 – were conducted while the accused were still in office. Some Republicans have questioned whether it’s even constitutional to conduct an impeachment trial of a former president.

But Michael Blake, a political philosopher at the University of Washington, explains that trying him is useful morally and politically, setting a boundary around the powers of the presidency, even if Trump can no longer be expelled from office:

“The impeachment of President Trump is an indication that there is a need to mark out, through a definitive statement, what no president ought to do. It will also set the moral limits of the presidency – and, thereby, send a message to future presidents.”

2. What happens if Trump is convicted?

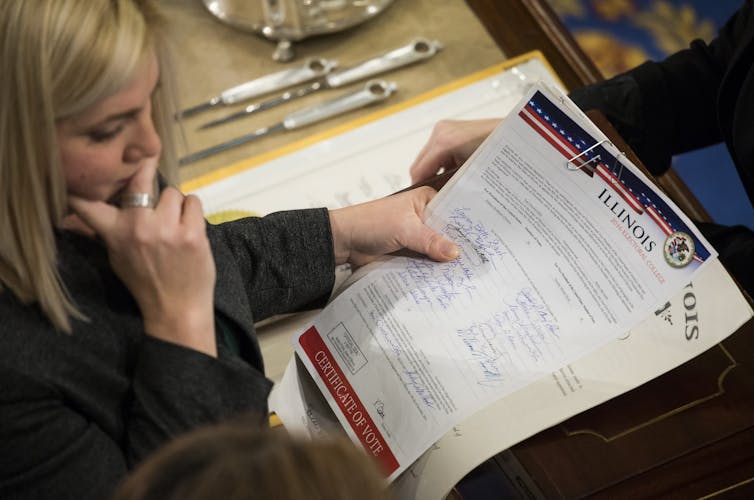

Though Trump can no longer be removed from office, he may still face consequences. Kirsten Carlson, a law professor at Wayne State University, explains that there is an additional step:

“The Senate also has the power to disqualify a public official from holding public office in the future. If the person is convicted …, only then can senators vote on whether to permanently disqualify that person from ever again holding federal office. … A simple majority vote is all that’s required then.”

3. What if he is not convicted?

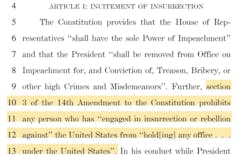

It is possible that two-thirds of the senators may not vote to convict Trump. But there is another way Congress might seek to bar Trump from holding office in the future.

Gerard Magliocca, a law professor at IUPUI, describes that approach, which would use Section 3 of the 14th Amendment. He writes that the amendment, created after the Civil War, bars people “from serving in a variety of government offices if they ‘shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion’ against the United States Constitution.”

However, it’s not enough for a majority of Congress to vote to declare Trump is ineligible to serve in office again, Magliocci explains: “only the courts, interpreting Section 3 for themselves, can bar someone from running for president.”

4. What is the real purpose of impeachment?

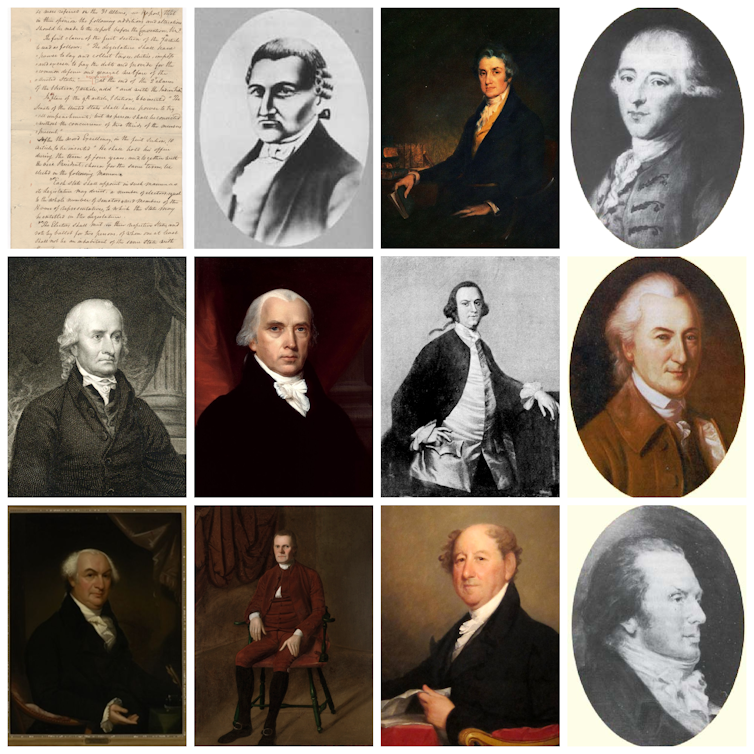

Even if immediate consequences are uncertain, the founders still understood that impeachment sent a powerful message, writes Clark Cunningham, a legal scholar at Georgia State University.

Based on his research into the people who wrote the Constitution and the statements they made at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, Cunningham explains that “the founders viewed impeachment as a regular practice with three purposes:

- To provide a fair and reliable method to resolve suspicions about misconduct;

- To remind both the country and the president that he is not above the law;

- To deter abuses of power.”

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]![]()

Jeff Inglis, Politics + Society Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.