<figure>

<img src="https://images.theconversation.com/files/488375/original/file-20221005-16-kkkvga.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&rect=11%2C0%2C3982%2C2700&q=45&auto=format&w=754&fit=clip" />

<figcaption>

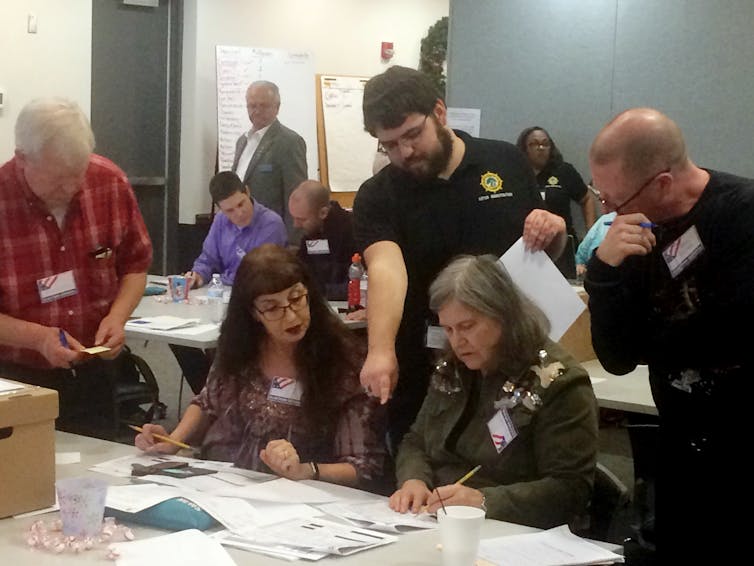

Voting at home by mail can be very convenient – and safe from concerns about COVID-19.

<span class="attribution"><a class="source" href="https://www.gettyimages.com/detail/news-photo/engineer-katherine-amoukhteh-looks-over-her-mail-in-ballot-news-photo/1052560438">Robyn Beck/AFP via Getty Images</a></span>

</figcaption>

</figure>

<span><a href="https://theconversation.com/us/team#jeff-inglis">Jeff Inglis</a>, <em><a href="http://www.theconversation.com/">The Conversation</a></em></span>

<p>As the midterm elections approach, much of life has returned to its <a href="https://time.com/6203058/covid-19-pandemic-return-to-normal-column/">busy post-COVID-19 normal</a>, even as <a href="https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/09/1126621">the pandemic continues</a>. Being busy and wary of sharing space with large numbers of strangers are among the many reasons people might consider skipping Election Day. </p>

<p>In most states, you can skip Election Day and still vote, though. In many ways, the most convenient way to vote is by mail – even if many states require you to file a form or use a website to request a ballot. You can examine the choices of candidates and questions, and consider your choices, as you would if you were to vote on Election Day. When you are ready, you can mark your ballot in your own time and either mail it back or drop it off at a local ballot drop box or government office – as long as you do it before your state’s deadline.</p>

<p>Many people have questions about the integrity of this process, how they can be sure their vote will be counted accurately and how they can make sure it is even counted at all. Several scholars have written articles for The Conversation U.S. describing aspects of this system and explaining why it’s trustworthy and safe.</p>

<figure class="align-center zoomable">

<a href="https://images.theconversation.com/files/358212/original/file-20200915-16-1t34hep.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=45&auto=format&w=1000&fit=clip"><img alt="A sample ballot from Cobb County, Georgia." src="https://images.theconversation.com/files/358212/original/file-20200915-16-1t34hep.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=45&auto=format&w=754&fit=clip" srcset="https://images.theconversation.com/files/358212/original/file-20200915-16-1t34hep.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=45&auto=format&w=600&h=900&fit=crop&dpr=1 600w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/358212/original/file-20200915-16-1t34hep.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=600&h=900&fit=crop&dpr=2 1200w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/358212/original/file-20200915-16-1t34hep.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=600&h=900&fit=crop&dpr=3 1800w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/358212/original/file-20200915-16-1t34hep.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=45&auto=format&w=754&h=1131&fit=crop&dpr=1 754w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/358212/original/file-20200915-16-1t34hep.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=754&h=1131&fit=crop&dpr=2 1508w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/358212/original/file-20200915-16-1t34hep.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=754&h=1131&fit=crop&dpr=3 2262w" sizes="(min-width: 1466px) 754px, (max-width: 599px) 100vw, (min-width: 600px) 600px, 237px"></a>

<figcaption>

<span class="caption">Ballots are specific to particular locations, including counties, municipalities and even sewer districts.</span>

<span class="attribution"><a class="source" href="https://newsroom.ap.org/detail/GeorgiaElection/5df9347ff905475baea828cb10f64299/photo">AP Photo/Amy Beth Hanson</a></span>

</figcaption>

</figure>

<h2>1. ‘Built-in safeguards’</h2>

<p><a href="https://charlottelhill.com/">Charlotte Hill</a>, a former local election official in San Francisco who now studies voting laws at the University of California, Berkeley, and political scientist <a href="http://jakegrumbach.com/">Jake Grumbach</a> from the University of Washington write about <a href="https://theconversation.com/6-ways-mail-in-ballots-are-protected-from-fraud-145666">six ways mailed ballots are protected from fraud</a>. Those include the facts that it’s very hard to make a fake ballot and a fake envelope and that eagle-eyed postal and municipal workers are always on the lookout for irregularities.</p>

<p>“The mail-in voting process has several built-in safeguards that together make it hard for one person to vote fraudulently and even more difficult to commit voter fraud on a scale capable of swinging election outcomes,” Hill and Grumbach write.</p>

<h2>2. Lessons from Oregon</h2>

<p>Since 1998, all elections in Oregon have been held by mail. Over that entire time, <a href="https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=OjANI8UAAAAJ&hl=en&oi=ao">Priscilla Southwell</a>, a professor emerita of political science at the University of Oregon, has watched how the system has worked and how people have reacted to it, and then she has analyzed its integrity.</p>

<p>“<a href="https://theconversation.com/mail-in-voting-lessons-from-oregon-the-state-with-the-longest-history-of-voting-by-mail-145155">Oregon’s experience shows that mail-in voting can be safe</a> and secure, providing accurate and reliable results the public can be confident in,” she writes.</p>

<p>Her conclusion reflects broad public support of the system: “Perhaps the strongest evidence that the system is equitable, fair, reliable and safe is that in two statewide surveys I have conducted over the years, a nearly identical percentage of Oregon Republicans and Democrats strongly support voting by mail, and the same is true of elected officials in the state.”</p>

<h2>3. One caution</h2>

<p>In an article crediting the convenience and integrity of voting by mail, political scientists <a href="https://www2.brockport.edu/live/profiles/1593-susan-orr">Susan Orr</a> of The College at Brockport, State University of New York, and <a href="https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=adNsL9sAAAAJ&hl=en&oi=ao">James Johnson</a> at the University of Rochester note one potential pitfall: Because it happens outside an official polling place, <a href="https://theconversation.com/voting-by-mail-is-convenient-but-not-always-secret-144716">the act of voting isn’t necessarily secret</a>.</p>

<p>A person voting by mail may be more susceptible to the influence of a relative, friend or employer, or may even be observed while marking their ballot. </p>

<p>“The voter marks the ballot outside the supervision of election monitors – often at home. It’s possible to do so in secret,” they explain. “But secrecy is no longer guaranteed, and for some it may actually be impossible.”</p>

<figure class="align-center zoomable">

<a href="https://images.theconversation.com/files/355617/original/file-20200831-25-1kwalj9.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=45&auto=format&w=1000&fit=clip"><img alt="A motorcyclist puts a ballot in a drop box." src="https://images.theconversation.com/files/355617/original/file-20200831-25-1kwalj9.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=45&auto=format&w=754&fit=clip" srcset="https://images.theconversation.com/files/355617/original/file-20200831-25-1kwalj9.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=45&auto=format&w=600&h=382&fit=crop&dpr=1 600w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/355617/original/file-20200831-25-1kwalj9.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=600&h=382&fit=crop&dpr=2 1200w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/355617/original/file-20200831-25-1kwalj9.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=600&h=382&fit=crop&dpr=3 1800w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/355617/original/file-20200831-25-1kwalj9.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=45&auto=format&w=754&h=480&fit=crop&dpr=1 754w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/355617/original/file-20200831-25-1kwalj9.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=754&h=480&fit=crop&dpr=2 1508w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/355617/original/file-20200831-25-1kwalj9.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=754&h=480&fit=crop&dpr=3 2262w" sizes="(min-width: 1466px) 754px, (max-width: 599px) 100vw, (min-width: 600px) 600px, 237px"></a>

<figcaption>

<span class="caption">Drop boxes can be a helpful alternative to mailboxes for people who prefer not to buy postage or who are voting at the last minute.</span>

<span class="attribution"><a class="source" href="https://newsroom.ap.org/detail/Election2020VoteByMailOregon/676bbd6939e64809be1cccf6d10d154e/photo">AP Photo/Don Ryan</a></span>

</figcaption>

</figure>

<h2>4. Some ignore the evidence</h2>

<p>There have been several lawsuits, especially in the wake of the 2020 presidential election, alleging that voting by mail is fraudulent or suspect. Rutgers University Newark law professor <a href="https://law.rutgers.edu/directory/view/venetis">Penny Venetis</a> has observed that some judges accept those claims:</p>

<p>“<a href="https://theconversation.com/mail-in-voting-does-not-cause-fraud-but-judges-are-buying-the-gops-argument-that-it-does-144157">Without providing any explanation or evidence to the contrary</a>, these decisions essentially erase scientific findings, cementing into law unsubstantiated and discredited claims linking voting by mail to fraud.”</p>

<h2>5. Easy accountability</h2>

<p>If you’ve decided to vote by mail, in most states you can keep tabs on your ballot and make sure it arrived safely at your local election office.</p>

<p>Law professor <a href="https://www.ali.org/members/member/429782/">Steven Mulroy</a> at the University of Memphis explained that many states have “<a href="https://theconversation.com/how-to-track-your-mail-in-ballot-148503">a unified system [that] allows all voters to see</a> when their request for a ballot by mail was received, when the ballot was mailed to them and when the completed ballot was received back at the local election office.”</p>

<p>Check to see if your state is one, and you can rest assured that your ballot is on the way, that you’ve successfully mailed it back and that it has been accepted and counted.</p>

<p><em>Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archive.</em><!-- Below is The Conversation's page counter tag. Please DO NOT REMOVE. --><img src="https://counter.theconversation.com/content/191988/count.gif?distributor=republish-lightbox-basic" alt="The Conversation" width="1" height="1" style="border: none !important; box-shadow: none !important; margin: 0 !important; max-height: 1px !important; max-width: 1px !important; min-height: 1px !important; min-width: 1px !important; opacity: 0 !important; outline: none !important; padding: 0 !important" referrerpolicy="no-referrer-when-downgrade" /><!-- End of code. If you don't see any code above, please get new code from the Advanced tab after you click the republish button. The page counter does not collect any personal data. More info: https://theconversation.com/republishing-guidelines --></p>

<p><span><a href="https://theconversation.com/us/team#jeff-inglis">Jeff Inglis</a>, Freelance Editor, <em><a href="http://www.theconversation.com/">The Conversation</a></em></span></p>

<p>This article is republished from <a href="https://theconversation.com">The Conversation</a> under a Creative Commons license. Read the <a href="https://theconversation.com/so-you-want-to-vote-by-mail-5-essential-reads-191988">original article</a>.</p>

![]()