The voters have cast their ballots, and after those ballots have been counted, and a winner has been projected by news organizations, that’s not the conclusion of the election. The actual outcome of the 2024 presidential election will be determined by the Electoral College.

The Conversation U.S. has had several articles explaining the history and effects of the United States’ curious method of choosing a president, not with one national election but with 51 smaller elections, in each state and Washington, D.C. Here are the highlights of that coverage.

1. A safeguard for democracy

The Electoral College was the result of a compromise devised among 11 men at the Constitutional Convention in the hot Philadelphia summer of 1787. It was meant as a protective measure against rule by an uninformed mob, as Purdue University social studies education professor Phillip J. VanFossen explains. He describes how electors came to cast the decisive votes for president, writing:

“(The) founders were reassured that with this compromise system, neither public ignorance nor outside influence would affect the choice of a nation’s leader. They believed that the electors would ensure that only a qualified person became president. And they thought the Electoral College would serve as a check on a public who might be easily misled, especially by foreign governments.”

2. Creating new danger

By contrast, though, Barry C. Burden, a political science scholar at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, found that rather than protecting American democracy, the Electoral College system created a new risk:

“Someone who wants to infiltrate the election system would have difficulty causing problems in a national popular vote because it is decided by thousands of disconnected local jurisdictions. In contrast, the Electoral College makes it convenient to sow mischief by only meddling in a few states widely seen as decisive.”

3. Protecting the popular vote?

There may be limits to that meddling, though. The Constitution allows state legislatures to choose the electors – which Donald Trump and his supporters tried to exploit in 2020 by asking Republican state legislators to appoint fake electors to confuse matters.

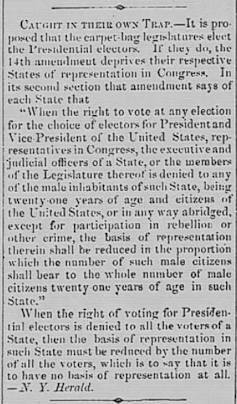

However, as Eric Eisner, a history Ph.D. student at Johns Hopkins University, and David B. Froomkin, a law professor at the University of Houston Law Center, explain, that would have run afoul not only of those states’ laws but also of another provision of the Constitution: The 14th Amendment says that if a state disenfranchises any of its voters, that state loses a proportional amount of its seats in the House of Representatives.

So, Eisner and Froomkin explain:

“(I)f a state legislature were to directly choose electors, that would disenfranchise all of the state’s voters. The right to vote, after all, is the right to have one’s vote counted, not the right to have one’s preferred candidate win. If all of a state’s voters have their right to vote taken away, Section 2 requires that the state’s House representation immediately and automatically be reduced to zero.”

That, in turn, means the state would only have two electors – and would no longer be a factor in the election.

4. Why does the US still have an Electoral College?

Other nations took a lead from the U.S. creation of the Electoral College, creating their own versions. But they didn’t last, as Westminster College political scientist Joshua Holzer explained:

“None have been satisfied with the results. And except for the U.S., all have found other ways to choose their leaders.”

Many people in the U.S. also have problems with the Electoral College, and Holzer identifies one effort underway to replace it without amending the Constitution. But even that wouldn’t ensure that the person who becomes president would be supported by at least half of the people who cast ballots.![]()

Jeff Inglis, Politics + Society Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.